This article was first published by The Roborant Review on January 6, 2026.

What is art? Is it personal or social? Must it communicate a conscious idea or emotion? Must it be beautiful or should it resist mainstream notions of beauty? Should it be transgressive? Sellable? How about the notion of art as a way to document experience, challenge prevailing perceptions, or connect with strangers?

There will always be arbiters who purport to regulate or authenticate what qualifies as art. Our own tastes tend to jump in as judge and jury. And yet, how can we be sure that our own biases aren’t limiting or occluding our vision? The only way to be sure is to challenge them. It’s in this state of mind that I entered The Asian Art Museum’s Rave into the Future: Art in Motion.

Already a fan of two of the featured artists, I didn’t doubt the quality of the work on show, but I wasn’t sure what to make of the unifying concept. If art has any purpose, perhaps it is the invitation to enter a world with which we are not already familiar. To be curious about what we don’t already understand is a deeply undervalued luxury.

Museums often rely on blockbuster shows of big-name artists to boost foot traffic. Scale and buzz become stand-ins for significance as the line between branding and scholarship is blurred. The spikier edges of challenging or political work are softened along the way. It was a delight, therefore, to visit a marquee museum and encounter edgy curatorial work that offered art as neither spectacle nor nostalgia.

The Asian Art Museum’s Rave into the Future: Art in Motion, curated by Naz Cuguoğlu, unfolds less like a linear argument than like a night out. Rather than flattening West Asian rave culture into a genre or aesthetic to be displayed or explained, the show traces its circulatory system, from pirate radio signals and cassette tapes passed hand to hand to living rooms that become temporary clubs.

This is not a show about nightlife aesthetics, however. The exhibition enacts the ways that diasporic communities from West Asia and beyond utilize rhythm, repetition, transmission, and pleasure to stay intact under pressure. In doing so, it rejects the dominant Western narrative that frames West Asia primarily through trauma, conflict, and spectacle. Instead, Rave into the Future insists that joy, humor, and sensuality are not distractions from politics but strategies within it.

Imagine that: pleasure as a political practice. The artists here don’t deny violence or displacement; they route around it, building counter-archives of collective release. Rave, one comes to feel, is not escapist but a means of survival. Bedrooms, broadcast towers, dancefloors, shrines, and after-parties emerge as parallel spaces where bodies gather, signal to one another, and rehearse futures for which languages, old and new, may be inadequate.

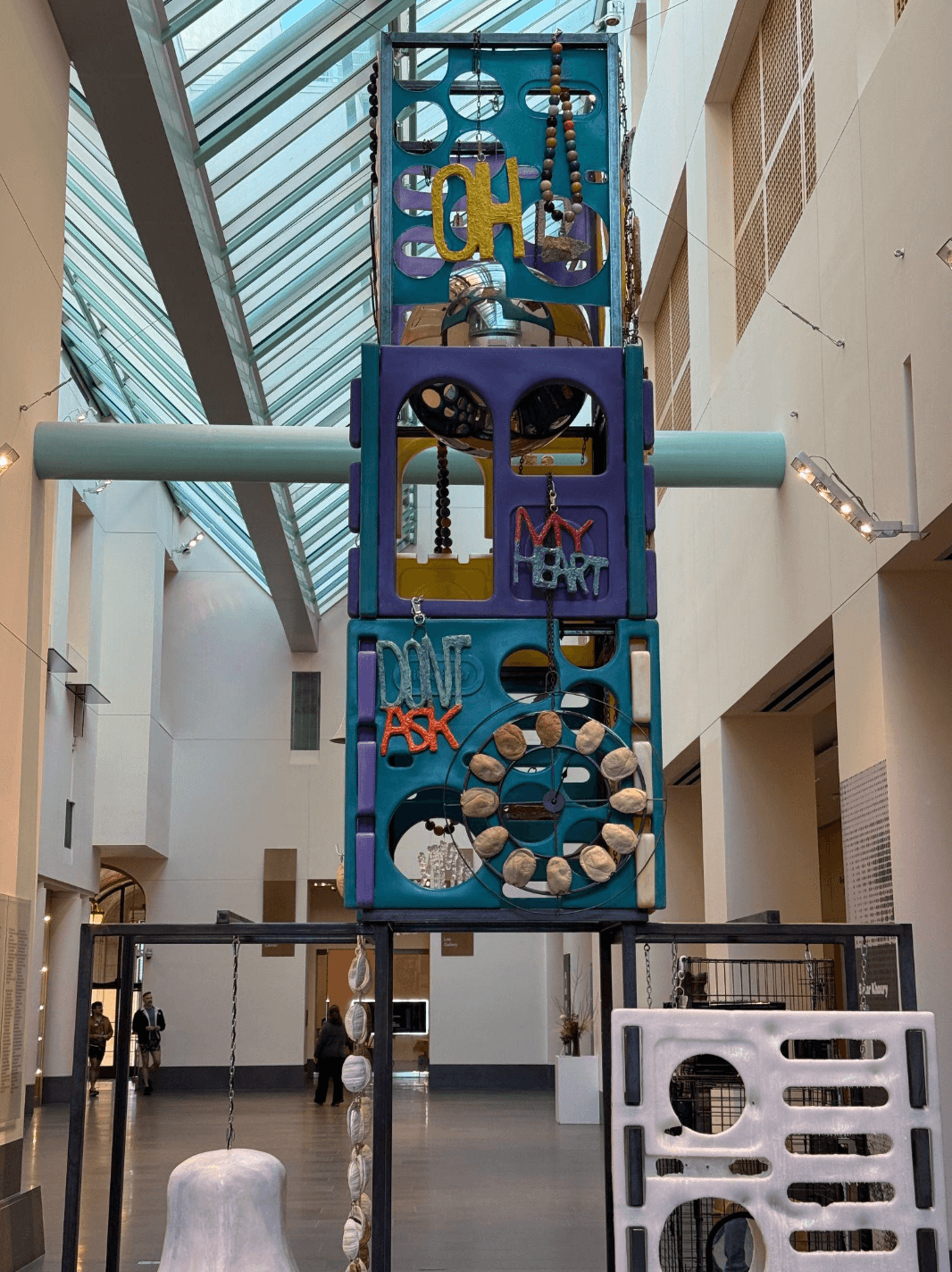

Before entering the safe rave space of the exhibition, the visitor is invited to walk beneath a twenty-foot installation, Sahar Khoury’s Untitled (radio tower with accessories). The question of who gets heard, and how, runs through the towering multimedia work, as a reminder that cultural memory is carried as much through unofficial or underground channels as through public monuments. There are evocations of Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum, whose voice traveled across borders via live radio broadcast to inspire listeners for nearly 40 years. It’s worth noting that at her funeral in 1975, the entertainer known as “The Fourth Pyramid” and “The Voice of Egypt” drew a crowd of over 4 million people.

Also playing through old school boom boxes is Khoury’s collaboration with sound artists Lara Sarkissian and Esra Canoğulları (8ULENTINA), in which she fractures and reweaves Umm Kulthum’s song-poem “Al Atlal (The Ruins), interspersing a recording of her late aunt singing at a family gathering. Khoury further replicates the gorgeous words that open Al Atal (The Ruins) in ceramic.

Oh my heart, don’t ask where the love has gone

It was a citadel of my imagination that has collapsed

Pour me a drink and let us drink of its ruins

Upon entering the exhibition pavilion, the healing begins with deep bass beats that sweep the visitor into the club’s pulse and onto a glowing dancefloor. Joe Namy’s Disguise as Dancefloor, a nearly 100-square-foot expanse of copper tiles, becomes both surface and living archive. Copper, a material associated with healing and sonic conductivity, turns the dancefloor into a recording device. The work invites visitors to grab a headset, jump in, and add their lightness of being to this ledger of presence. Every footfall leaves its mark.

If Namy’s dancefloor is the exhibition’s physical anchor, Sahar Khoury’s multimedia sculpture functions as its nervous system. The installation supports a functioning deck, where local Asian and diasporic DJs act as caretakers whose role is not to showboat, but to modulate energy, read the room, and hold space for community. It’s composed of old animal cages. One can imagine the sound of animals calling to be released and set free. The human echo is captured in such gestures as a spiked ceramic heart suspended within one of the cages.

Yasmine Nasser Diaz’s For Your Eyes Only distills generations of dance culture into a single bedroom scene. Projections of female and non-binary dancers clipped from social media loops alongside a grainy ’90s television playing footage of women-led protests across the Global South. Pink neon, a rose-colored disco ball, and scattered protest ephemera straddle the line between domestic safety and political urgency.

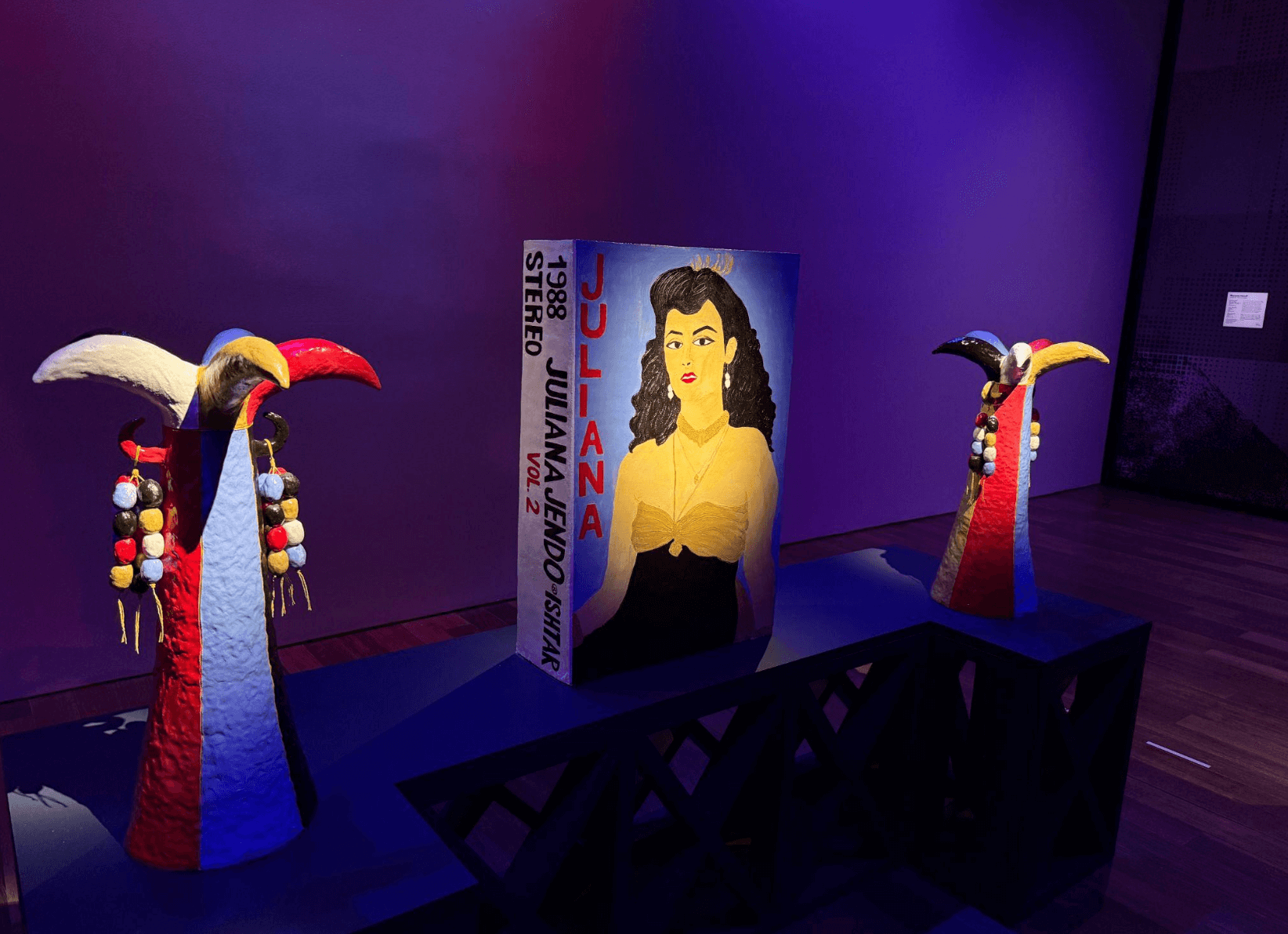

Maryam Yousif extends this question of transmission and legitimacy with a sculpture that elevates the mixtape, once a primary vector of diasporic circulation, into an oversized monument. Named after the production company Ishtar, itself a reference to the ancient Mesopotamian goddess, the work collapses myth, pop culture, and personal memory into a single form. It refuses the idea that what is mass-produced or ephemeral cannot also be sacred.

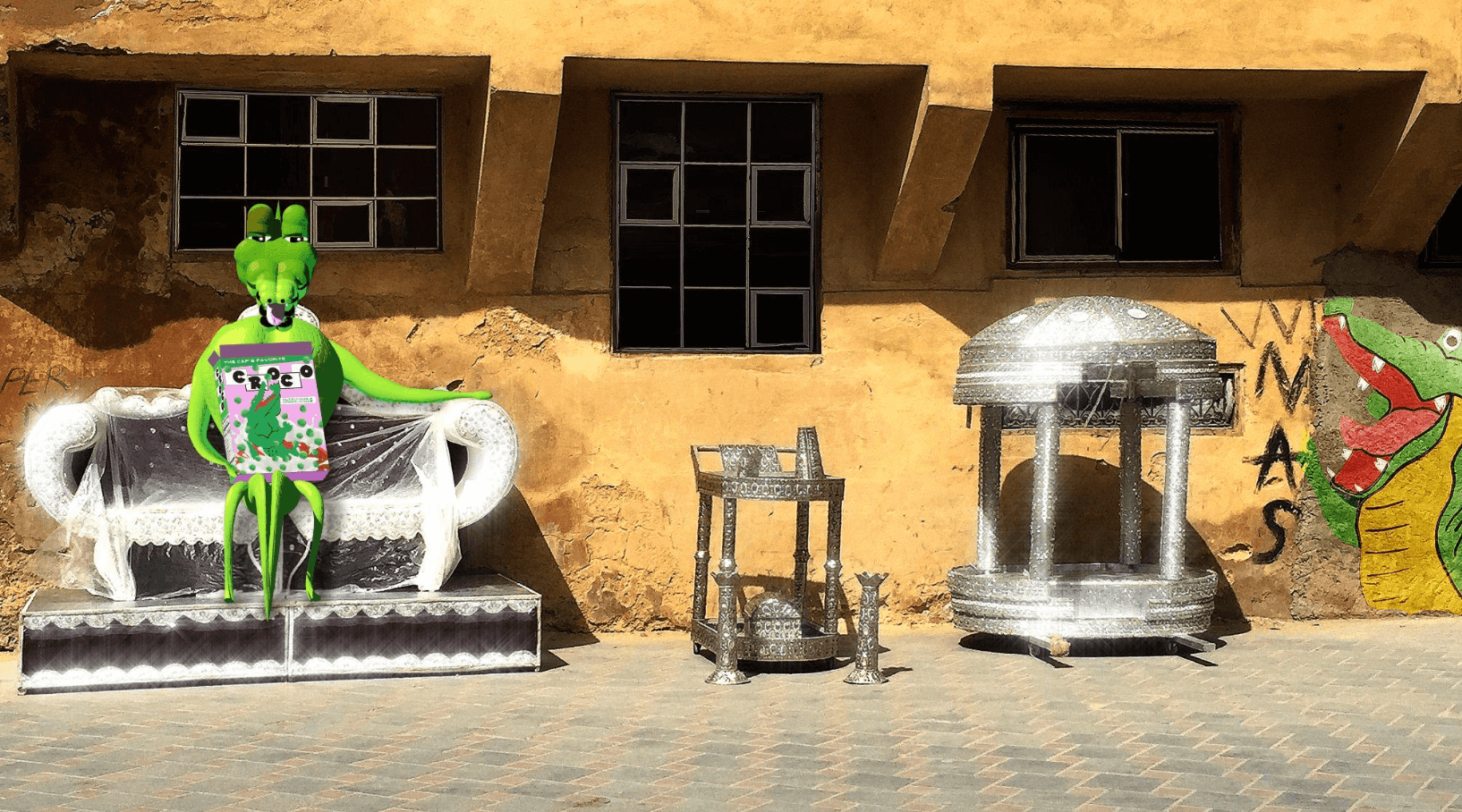

Several video works lean into the surreal humor central to rave culture’s refusal of respectability. Meriem Bennani’s Party on the CAPS follows Fiona, a talking crocodile, through a futuristic refugee camp where teleportation has replaced air travel. In Spiral, a collaboration between Sophia al Maria and Fatima al Qadiri, a belly dance–off becomes an assertion of queer defiance, body sovereignty, and pleasure as resistance.

Farah Al Qasimi’s Um Al Naar (Mother of Fire) takes the form of a horror-comedy, centering a jinn who fears becoming irrelevant and reclaims her place through dance. Morehshin Allahyari’s The Queer Withdrawings features reflective surfaces animated by a dance of protective mythical figures, suggesting that rave culture’s trance aspects and collective care overlap with spiritual practice.

In all these works lies an absurd and tender reminder that joy doesn’t disappear under surveillance; it mutates.

The exhibition ends where raves often do: in glitter and aftermath. In Puff Out, :mentalKLINIK unleashes robotic vacuum cleaners across a floor blanketed in sparkle. The machines wander, redistribute, and refuse the notion of cleanup as closure. A rave, it seems, doesn’t end; it simply disperses. The traces it leaves behind resist containment. This is a revolutionary concept.

What Rave into the Future: Art in Motion reveals is that rave culture is not an escape from reality but a rehearsal for it. It is where diasporic communities test ways of being together, through sound, movement, humor, and resistance, when official systems fail. By allowing that ethos to seep into the museum without fully domesticating it, the exhibition makes a compelling case for the dancefloor as a site of personal and societal transformation.

The exhibition runs from Oct 24, 2025 – Jan 26, 2026, at The Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. The artist list includes: Morehshin Allahyari, Sophia al Maria, Farah Al Qasimi, Fatima Al Qadiri, Meriem Bennani, Yasmine Nasser Diaz, Sahar Khoury, :mentalKLINIK, Joe Namy, and Maryam Yousif.